Has the father-son bond always been wounded, or is this a relatively new phenomenon in human history? While it is hard to establish exactly what the father-son relationship was like in earlier ages, there is evidence that structural changes in the way industrialised societies have organised their economies have had a major impact.

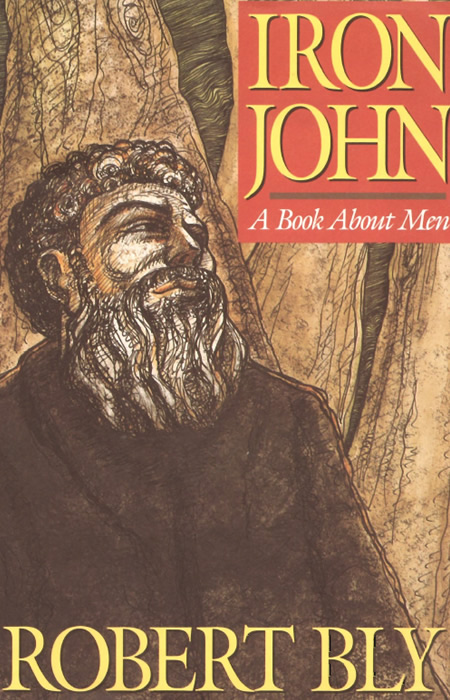

Robert Bly, who explores the father-son relationship in his book Iron John, suggests that the Industrial Revolution was a significant turning point in the relationships between fathers and sons. Bly points out that before the Industrial Revolution a son participated in what his father did. He worked with his father. He shared in his father’s world. He saw what his father did and how he spent his time. Bly contends that because they worked together, the son felt validated by his father. That is, a son did not have to spend the rest of his life earning his father’s respect, because he already had it. He already had a domain in which he had credibility, in which he was accepted, in which he knew he had gifts. In short, he didn’t have to prove himself as a man.

This sort of family economy where a father trained his son, and then worked with him, existed in rural Europe and America until the end of the eighteenth century when the Industrial Revolution wrought huge changes in societal and family structures. Father and son business partnerships disappeared as men, women, and children began working in factories and mines. The hours and the conditions under which they worked disrupted the then-existing patterns of family life.

As the work situations have continued to evolve, sons now have less access to their fathers than they did two hundred years ago. Fathers are often precluded from child-rearing by a work routine that takes them out of their homes for much of the day and into the night. As a result, a void has developed in the father-son relationship because sons don’t see how their fathers react and cope at their workplace, so they don’t really know who their fathers are. This lack of sufficient and meaningful contact with their fathers is detrimental to the sons’ development of a healthy masculine self-image. Consequently, when these adolescents grow to manhood, many of them have a false or insufficient understanding of what it means to be a man. They define themselves by career, status, and possessions—in other words, by what they do, who they know, and what they own, rather than by who they are. This, in turn, affects their relationships with their wives, with their daughters, with other men and women, and, particularly, with their own sons.

This program encourages a conversation between fathers and sons that will in great part repair any lack of communication between fathers and sons.